Wittgenstein writes, ““It’s as if we could grasp the whole use of a word at a stroke.” — Well, that is just what we say we do” (§191). Can the mind actually summon all of the uses to which a word might be put at a stroke? When do we imagine that this is so? Pivoting from the question of how “a word” could contain all its possible uses to how “a machine” could contain all of its possible motions, Wittgenstein insists that we talk this way when we are “doing philosophy” (§194).

While it’s unclear to me whether Wittgenstein has particular philosophies in mind, I find it interesting to think about the “possibility of a machine’s motion” as an idea of metaphysics—the discourse of philosophy concerned with the first causes of “machines” like physical systems and human bodies. If we accept the premise that the “machine seems already to contain its own mode of operation,” (§193) then the initial picture of the machine that the philosopher gives becomes the basis of “a series of pictures.” Hobbes’ picture of the human driven by means-ends logic contains within it the possibility of a whole series of pictures of humans acting out of self-interest. Alternatively, we can derive from the theological picture of a machine run by a God given moral sense a whole series of pictures of humans acting benevolently.

Wittgenstein insists that this kind of talk is figurative—“the movement of the machine qua symbol is predetermined in a different way from how the movement of any given actual machine is” (§193). We would not insist that the motions of a human being that we have some actual experience with are pre-determined, because we know that, however predictable that person may be, s/he is liable to move in all sorts of unforeseeable ways. To present a picture of human nature as a machine that contains all of its possible motions ahead of time (as was common in the Enlightenment) is to present a symbol that bears no necessary relation to our everyday experience of others. Wittgenstein carves out a space here for poetic thinking, but insists that the use of symbols in philosophy leads to “misinterpretations.” Philosophical discourses that aspire to holistically describe how the world works fail to understand their own grounding in the potentially wayward imagination.

When Wittgenstein indulges his own imagination that “infinitely long rails correspond to the unlimited application of a rule” (§218), he notes, “I should say: This is how it strikes me.” The image giving expression to this infinite process may only “strike” the “I” who offers it. In this philosophy, one cannot assume that symbols are shared. If the modern discourse of metaphysics is grounded in symbolical propositions guised as truth claims, then who is to say that it does what it says that it does; that is, speak objectively about the world? When we adequately account for symbolic status of metaphysical claims, they may come to look like the arbitrary conjectures that happen to strike the philosopher as he sits alone in his study. Or, alternatively, the “false interpretation[s]” and “odd conclusions” of “primitive people” about civilized talk (§194). By turning attention to “language-games” observable in everyday life, Wittgenstein seeks to write a philosophy grounded in shared rules, rather than in symbols and false interpretations imposed from an ‘outside.’

David Hume shares Wittgenstein’s conviction that philosophy must speak of customary rules. There are very obvious differences between them: for Hume, the passions are what people share; for Wittgenstein, it’s language. But Hume’s thinking on promises converges with Wittgenstein’s on intention. Hume argues that it makes no sense to say that the obligation to keep a promise originates with a self-constituted intention. Instead, promises entail a sense of duty because of “the conventions of men”—our shared institution of “symbols and signs, by which we might give each other security of our conduct in any particular incident.” When Wittgenstein asks, “what kind of super-rigid connection obtains between the act of intending and the thing intended?” he turns to the example of a kind of promise—the statement “Let’s play a game of chess”—and insists that the connection between these words and the act can only lie “in the list of rules of the game, in the teaching of it, in the everyday practice of playing” (§197).

I bring up Hume because I think he makes a good foil for Wittgenstein. Whereas Hume and Wittgenstein share a weariness of certain solipsistic tendencies in Western philosophy, Hume’s turn to social convention involves an extensive delineation of the rules governing the occupation, prescription, accession and succession of property. Wittgenstein, on the other hand, turns to seemingly trivial practices of everyday life—to the game of chess, for example—and thus presents a philosophical optics is finer grained and less interested in serving the interests of power. Last class, Josh noted that the contingency of language games opens up the possibility that they can be other. By avoiding the kinds of generalities that Hume falls into, Wittgenstein seems also to avoid placing a stake in the conservation of any particular institution–like that of property, the family, or the state. Is this an evasion on Wittgenstein’s part?

The comparison with Hume is very apt – as is your calling attention to the very different ways in which they instantiate “the conventions of men.”

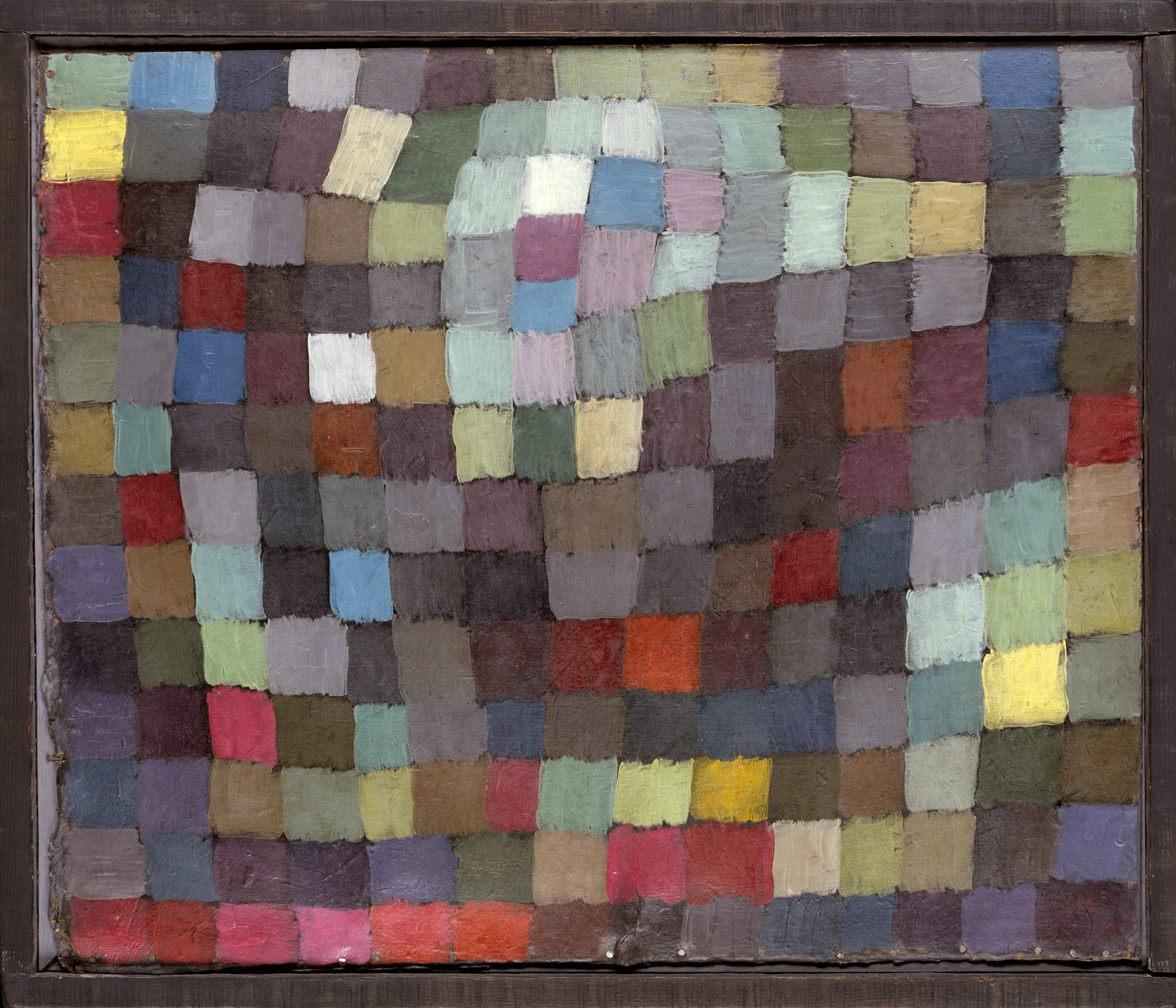

Regarding the use of “symbols” in philosophy, and your passing thought that “Wittgenstein carves out here a space for poetic thinking,” one difference might be that philosophy (or “metaphysics”) as Wittgenstein criticizes is blind to the symbol as symbol (as figure) – the picture of a machine is invested with all the rigidity of a machine, even more. Compare with this the beginning of the Dickinson poem:

A clock stopped –

Not the Mantel’s –

Geneva’s farthest skill

Cant put the puppet bowing –

That just now dangled still. –