We must have belief and meaning, but language cannot necessarily explain itself on these matters. This way of thinking follows Wittgenstein’s decision that the Tractatus Logico-Philisophicus was a failure and his discovery that the grammatical foundations for propositions are not logically certain. What we get in the Philosophical Investigations is fragmented remarks, which read like the philosopher’s unresolved conversation with himself. Wittgenstein aims to figure out what is meant by propositions about (among other things) understanding, seeing, feeling pain. He rejects the idea that such words ought to refer to some mysterious process of mind, preferring to understand them as they are used in particular “language games,” as he calls them. Language games are highly contingent—they are governed by potentially changeable rules—and the job of the philosopher is to give a good account of the empirical contexts that make these language games meaningful forms of communication.

Philosophy should speak about what it is possible to think and disabuse us of illusions–the deformities in our understanding–that language traditions themselves create. When one does philosophy this way, transcendental essences dissolve, as do static and uniform meanings for particular words. Words function differently in different contexts—sometimes words suggest to us a vivid picture, but other times they do not. Sometimes we think before we speak, and other times we do not. Expressive statements, like a cry of pain, do not necessarily call up a picture in our minds. A statement like “I’ve figured it out!” should be understood as a dynamic signal and not as a representation in the mind.

As Wittgenstein positions the signifier prior to the signified, he discovers that language’s relation to its outside (the empirical world of material objects, affects, sensations) is tenuous. The text deals with the strangeness of language, its epistemological ambiguities. Wittgenstein thematizes this point like a true skeptic by returning to the feasibility of simulation. Grown ups are trained to lie, to say what they do not mean, and it is sometimes hard to ascertain pretense from authenticity.

Wittgenstein rejects the idea that we have ‘special senses’ that produce their own special feelings. (Contrast this with the pleasurable free play of the faculties in Kant’s ‘Analytic of the Beautiful’) Because the concept of observation implies a pre-existent object, it cannot bring its own object into being. We may give a descriptive account of our observations about how our present sense of self differs from a sense of self in a past, but we cannot spontaneously constitute a sense of self by observation. This is because observation—like language itself–imposes a temporal frame.

Wittgenstein suggests that observations about the self are grounded in difference and, because of this, language is limited in its ability to describe the feeling of self-sameness. He continuously runs up against the difficulty of giving a description in language of the now, of the present moment, of the experience of simultaneity and presence. This difficulty recurs in his commentary on spontaneous motion. Here, he notes that, in most cases, we do not think, or form a picture, of our arm rising when we move our arm. It is difficult for us to describe this spontaneous process without inviting misconceptions (like about human ‘free will’). The instability of the ‘self’ is further underlined in the parts of PI where Wittgenstein obsessively returns to the fantasy of the ‘private language.’ The idea that we might all have access to our own idiosyncratic language of sensation–a way of knowing this feeling from that one yesterday–falls apart upon investigation. All this may explain the fragmented form of the remarks as well as Josh’s conviction that the text is one about ‘thinking in pieces.’

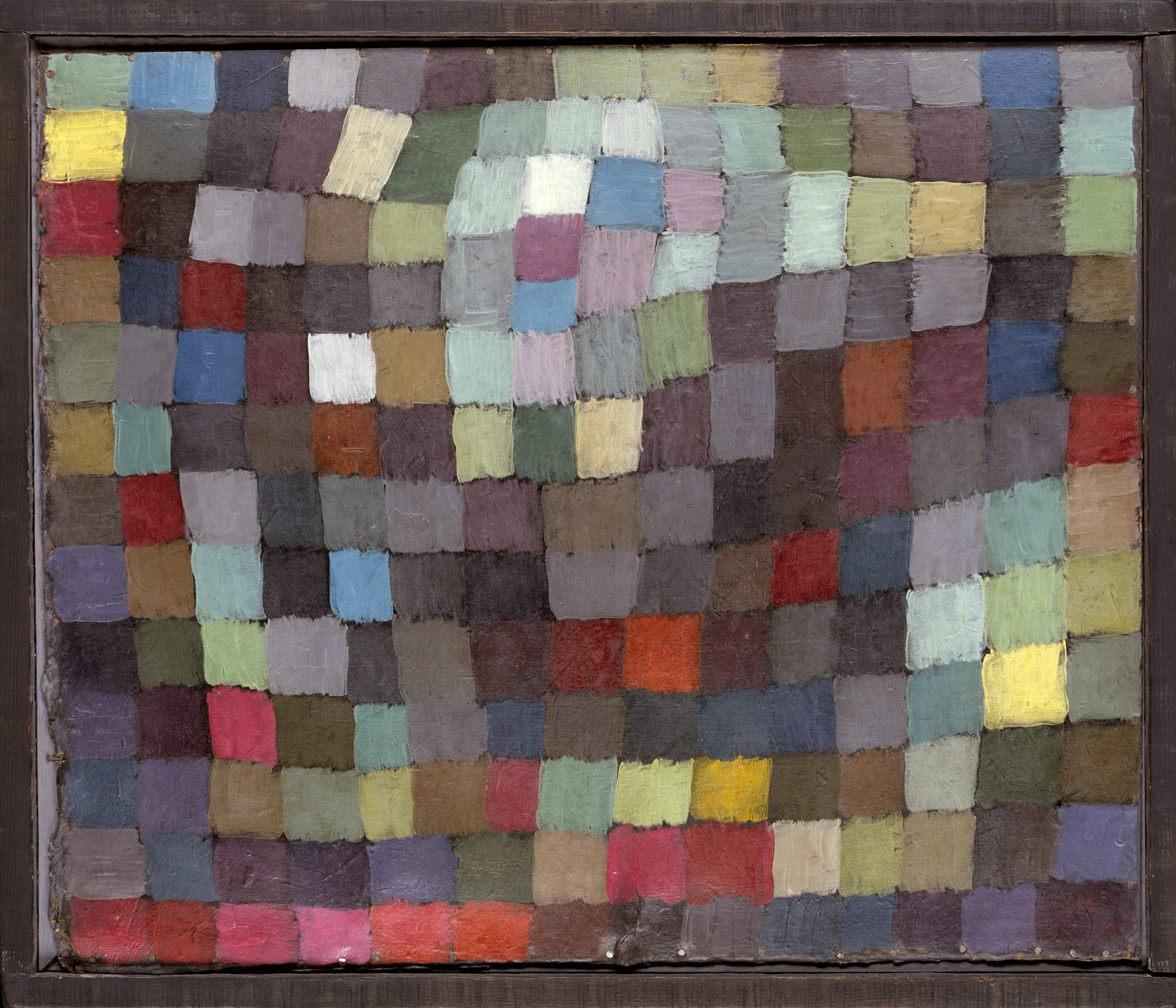

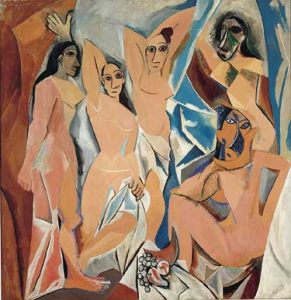

Wittgenstein’s insistence that language and thought do their work inside of time and space also informs his commentary on what it means to “see something” in a painting. Here, Wittgenstein dissolves the illusion that we can spontaneously grasp the whole of a painting. We can only observe one aspect of a picture at a time. There is no singly valid way of ‘seeing’ a picture—no authoritative model from which false ways of seeing would fall away. Instead, we see only pieces and sometimes become newly aware of some aspect of the picture, of it’s spatial organization. Compare this to Cubism in painting.

Joan’s suggestive comment is that we add aspects to our account of language games just as we add aspects to our visual interpretations of paintings. This implies that the space of freedom and flexibility that seems to disappear as Wittgenstein disrupts fantasies of mental processes and private feelings lies with our collective power to add aspects to the language games–to play with the rules.